Rites

Diurnal

The ritual language of Perístanom is Modern Indo-European. A follower of the religion is known in the language as Soqjá [/sɔkwˈja/] 🔊 (feminine), Soqjós [/sɔkwˈjɔs/] 🔊 (masculine), Soqjóm [/sɔkwˈjɔm/] 🔊 (neuter), or Soqjx́ [/sɔkwˈjɛks/] 🔊 (gender-neutral). Each gender-inflected form of the word soqjós means ‘the comrade’, ‘the ally’, ‘the associate’, or ‘the companion’. The plural forms are Soqjás [/sɔkwˈjas/] 🔊 (feminine plural), Soqjós [/sɔkwˈjos/] 🔊 (masculine plural), Soqjá [/sɔkwˈja/] 🔊 (neuter plural), and Soqjx́s [/sɔkwˈjɛksɪz/] 🔊 (gender-neutral plural). An adherent may also be known informally as a Peristanist.

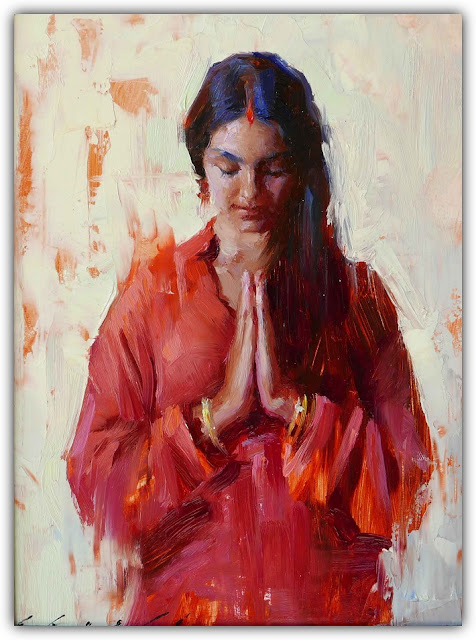

Whenever two or more Perístanos Soqjós [/pɛˈrɪstanɔs sɔkwˈjos/] 🔊 (‘the comrades of the religion’) come together in ritual fellowship, it is known as Kómnom [/ˈkɔmnɔm/] 🔊 (‘the meeting’ or ‘the gathering’). When they greet each other, they might exchange the phrase “Sucmtós tu!” [/sʊgwmˈtɔs ˈtu/] 🔊 (“Welcome to thee” singular/familiar), or the phrase “Súcmtos juwes!” [/ˈsʊgwmtos ˈjʊwɛs/] 🔊 (“Welcome to you!” plural/formal). More casually, they might say “Ala!” [/ˈɑla/] 🔊 (“Hello!”). When they part company, they might use the word “Rtís!” [/rˈtɪs/] 🔊 (“Farewell!”). More generally, they may exchange with reverence the phrase “Bheugor tebhei!” [/ˈbhɛʊgor ˈtɛbhɛɪ/] 🔊 (“I bow to thee!” singular/familiar), or the phrase “Bheugor jusméi!” [/ˈbhɛʊgor jʊsˈmɛɪ/] 🔊 (“I bow to you!” plural/formal). The latter two phrases are similar in their use to the Sanskrit words “Namaste!” and “Namaskar!” respectively, accompanied as well by the hand gesture of prayer, Añjali Mudrā, as in the traditional Hindu greeting shared for millennia.

Or perhaps Soqjós might exchange the phrase “Déiwos téwijos aisskans leínt!” [/ˈdɛɪwos ˈtɛwɪjɔs ˈɑɪsskans lɛˈint/] 🔊 (“May the gods grant thy wishes!” singular/familiar), or “Déiwos userós aisskans leínt!” [/ˈdɛɪwos ʊsɛˈrɔs ˈɑɪsskans lɛˈint/] 🔊 (“May the gods grant your wishes!” plural/formal). Or they might instead exchange the phrase “Déiwos tewóm aisdaint!” [/ˈdɛɪwos tɛˈwɔm ˈɑɪzdɑɪnt/] 🔊 (“May the gods honor thee!” singular/familiar), or “Déiwos jusmé aisdaint!” [/ˈdɛɪwos jʊsˈmɛ ˈɑɪzdɑɪnt/] 🔊 (“May the gods honor you!” plural/formal).

Soqjós may meditate daily at some peaceful time and place, either alone or in small groups, to commune with one or another of the various goddesses and gods of Déiwos—or with the supreme goddess Óljamma herself—and seek guidance, encouragement, affirmation, understanding, wisdom, hope, mercy, life, truth, love, peace, and faith. A small, spherical object—made of lead-free glass, or (oak) wood, ceramic, nontoxic metal, cloth, plastic, rubber, or other transparent, translucent, or opaque material—might be used to represent Déiwom Gola and assist in meditation, particularly on special, ceremonial occasions.

To express greetings in prayer to a specific goddess or god—to Óljamma, for example—Soqjós might declare “Ghéusete, Óljamma!” [/ˈghɛʊsɛtɛ ˈɔlˌjɑmma/] 🔊 (“Hear me, Óljamma!”). And to bid farewell to her in prayer, Soqjós might declare “Slwéjete, Óljamma!” [/slˈwejɛtɛ ˈɔlˌjɑmma/] 🔊 (“Hail, Óljamma!”). Soqjós may address the gods by name, or instead as “Dómuna” [/ˈdɔmuna/] 🔊 (“O Lady” feminine), “Dómune” [/ˈdɔmunɛ/] 🔊 (“O Lord” masculine), or “Dómunom” [/ˈdɔmunɔm/] 🔊 (“O Liege” neuter). The plural forms are “Dómunas” [/ˈdɔmunas/] 🔊 (“O Ladies” feminine plural), “Dómunos” [/ˈdɔmunos/] 🔊 (“O Lords” masculine plural), and “Dómuna” [/ˈdɔmuna/] 🔊 (“O Lieges” neuter plural).

Soqjós may conclude a session of prayer or meditation with the wishful word “Sjet” [/ˈsjet/] 🔊, which means “May it be”. It is similar in its use to the Abrahamic affirmative “Amen”, although an admittedly more accurate translation of this latter word into Modern Indo-European might be “Estod” [/ˈɛstot/] 🔊 (meaning “So be it”), or perhaps “Da” [/ˈda/] 🔊 (meaning “Certainly”). However, a preference for the optative mood over the imperative mood reflects a general attitude within Perístanom toward prayer that is more contemplative and receptive than arrogant or demanding.

Soqjós may routinely wear Médjotorqis [/ˈmɛdjɔˌtɔrkwɪs/] 🔊 (‘the acorn pendant necklace’), symbolizing nascent potential and its active nurturing. (The pendant should be worn on a lanyard with a breakaway closure for safety.) During important rituals, soqjós might choose to wear Ghelwa Togá [/ˈghɛlwa tɔˈga/] 🔊 (‘the green garment’), a cowled robe or tunic (e.g., a conventional hoodie) that is the verdant color of life.

To promote physical and emotional health, as their abilities permit and in consultation with medical professionals, Soqjós may each day perform aerobic exercise—such as walking for some time within a relaxing, safe, and preferably natural environment, in the morning or evening, perhaps after a meal, and with or without Sponos [/ˈsponɔs/] 🔊 (‘the walking stick’)—humble, oaken. Meditation, either formal or informal, may be incorporated into the routine of exercise. For discipline, focus, exercise, and particularly defense, a few ambitious Soqjós might choose to study mixed martial arts, modern pankration, or perhaps bartitsu, if appropriate to their individual health, abilities, and goals.

Before a meal, Soqjós may express gratitude toward those plants and animals who were sacrificed for nourishment, perhaps invoking the goddesses Dhéghom Matér and Áusos for any plant foods being consumed, and the gods Páuson and Máwort for any animal foods being consumed. Gratitude may be expressed with the phrase “Prijéjo jusmé!” [/prɪˈjejo jʊsˈmɛ/] 🔊 (“I thank you!” plural/formal), or the phrase “Prijéjomos jusmé!” [/prɪˈjejɔmɔs jʊsˈmɛ/] 🔊 (“We thank you!” plural/formal).

Soqjós may avoid processed foods where practical—processed flours, excess added sugars, artificial ingredients, industrial preparation, pesticides, etc.—in favor of a wide variety of whole foods providing complete nutrition, preferably organic and prepared in the home. If food from humane and sustainable animal husbandry is practically unavailable, vegan meals may be seen as a responsible option, in recognition of our kinship with all creatures. If so, however, particular care must be taken to ensure everyone’s diet includes all biologically necessary nutrients (e.g., complementary proteins). A multivitamin may be helpful for obtaining sufficient micronutrients, but it should be noted that even a supplement that claims to be “complete” may lack some of even the most essential vitamins (e.g., thiamine).

Soqjós may routinely offer some form of service to their fellow human beings and to other sentient and living creatures. The service, which may take myriad forms, is in recognition of the sacredness of us all. It demonstrates our solidarity with one another, particularly with those systematically impoverished, oppressed, and marginalized. We work to alleviate the suffering of others and of ourselves. The role of a Soqjós then is to strive to reduce the overall level of suffering in the world—from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs. We are communal by nature; when we help each other, we promote community within the sacred and realize our truest selves.

Occasional

Soqjós may employ the ceremonial Gaian calendar.

Soqjós may celebrate the changing of the seasons every year at the solstices and equinoxes. On the day of the hibernal solstice, they might celebrate Ghimós Latom [/ghɪˈmɔs ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (‘the day of the winter’) and invoke the godling Élba. On the day of the vernal equinox, they might celebrate Wesntósjo Latom [/ˌwesnˈtɔsjɔ ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (‘the day of the spring’) and invoke the maiden goddess Príja. On the day of the estival solstice, they might celebrate Sámosjo Latom [/ˈsɑmɔsjɔ ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (‘the day of the summer’) and invoke the mother goddess Pltáwija Matér. On the day of the autumnal equinox, they might celebrate Osnós Latom [/ɔsˈnɔs ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (‘the day of the autumn’) and invoke the elder deity Bhrghóntija. Note that the dates of these festivals will differ in the northern and southern hemispheres because of the different times of the year whereat each hemisphere’s seasons come. The first day of every year, 1 Mahina on the Gaian calendar, is celebrated as Néwosjo Átnosjo Latom [/ˈnɛwɔsjɔ ˈɑtnɔsjɔ ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (‘New Year’s Day’), with “Ghoilom newom atnom!” [/ˈghɔɪlɔm ˈnɛwɔm ˈɑtnɔm/] 🔊 (“Happy new year!”) being a benediction proper to the occasion.

In Perístanom, five developmental transitions from one primary stage of life to the next are recognized as typical, with suggested rites (and associated classical elements)—birth (water), initiation (earth), union (fire), culmination (air), and death (spirit):

1. Childbirth among Soqjós is called Sutus [/ˈsutʊs/] 🔊 (‘the birth’), or Sutéwos Admn [/suˈtɛwɔs ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the birth’), whereof the circumstances are to be determined by the mother giving birth. The anniversary of one’s birth is called Sutéwos Latom [/suˈtɛwɔs ˈlɑtɔm/] 🔊 (the ‘birthday’), wherefor the date is calculated annually as falling the same number of days after the date of the previous southern solstice as had correspondingly transpired the year of one’s birth. (The conventional custom of celebrating one’s birthday on a particular day recurring on any solar calendar may instead be observed). On or about the tenth day after the birth of a child, a naming ceremony might take place. During the event, the infant might be ceremonially bathed, in keeping with the needs and wishes of the infant. Meditative prayers might be offered by a Peristanist parent or both parents, invoking a favorite goddess or god, perhaps Élba, expressing gratitude, and hopes for long life, health, happiness, grace, or similar appeals. The child’s personal name may be declared before family and friends. The ceremony is called Práinomenos Admn [/ˈprɑɪˌnomɛnɔs ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the given name’) and resembles infant baptism, symbolizing the ancient origins of life in water. It is meant to help the child recall in life the ancient wisdom of primordial ancestors.

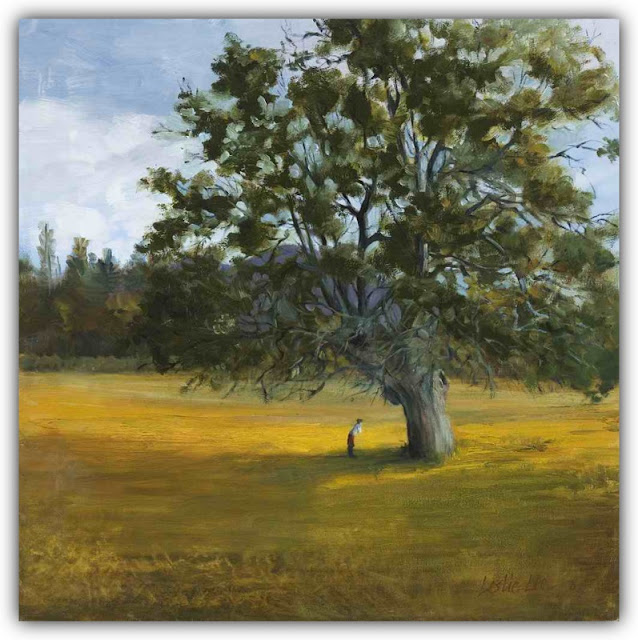

2. When a young Soqjós reaches adulthood, a point of psychological self-responsibility and maturity—at some age between fourteen and twenty-one years, depending upon the individual and the society—a ceremony might be held, among family, friends, and perhaps the entire community, when the youth might plant a tree—such as an oak or some other favorite variety of tree—in the earth at some location that is personally regarded as sacred or special. Meditative prayers might be offered, invoking a favorite goddess or god of Déiwos, perhaps Príja, Pérqunos, or Mánus, and expressing hope that the youth might find a calling in life. The ceremony is called Áltjosjo Admn [/ˈɑltjɔsjɔ ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the adult’).

3. On the occasion of a Peristanist wedding or handfasting, the couple (of any genders) will each light a separate candle, representing their two individualities. Declarations of the couple’s mutual commitment may be offered to the community, invoking their respective favorite goddess or god, perhaps to Pltáwija Matér, Djéus Patér, Ménots, Sáwel, or Mánus. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the couple will use their individual candles to simultaneously light a central candle, representing their union, and then extinguish the two individual candles. The ceremony is called Wedhmn̥ [/ˈwɛdhmn/] 🔊 (‘the wedding’), or Wédhmenos Admn [/ˈwɛdhmɛnɔs ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the wedding’).

4. On the occasion of the retirement from a career, the retiring Soqjós might cultivate a butterfly, to be ceremonially released into the air. During the ceremony, a favorite goddess or god might be invoked, such as Pltáwija Matér, Dhéghom Matér, or Bhrghóntija. The ceremony is called Édhlosjo Admn [/ˈɛdhlɔsjɔ ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the elder’).

5. On the occasion of the funeral of a Soqjós, the body of the departed is traditionally buried in the earth as a reclaiming of the remains within the cycle of life. A poem or scriptural passage that was personally regarded as sacred or special to the deceased might be read among the community by a close friend or member of the family. The community bids goodbye to the departed with the recognition that someday, in the far distant future, they will all have the opportunity to be together again—ultimately within Peridhóighos (Paradise), when life will have been perfected, free of pain, anguish, and suffering. Meditative prayers might be offered, invoking a favorite goddess or god of the deceased, or perhaps Wélnos or Kréuna—or Bhrghóntija, who will convey the person’s etmn [/ˈɛtmn/] 🔊 (‘the soul’ or individual pattern) across the waters of Pósticita [/ˈpɔstɪˌgwita/] 🔊 (‘the afterlife’) and into Déiwos. The ceremony is called Dheunos [/ˈdhɛʊnɔs/] 🔊 (‘the burial’), or Dhéunesos Admn [/ˈdhɛʊnɛsɔs ˈɑdmn/] 🔊 (‘the rite of the burial’).

This website employs both the Metamorphous display typeface and the Gentium Plus body text typeface, whereof the latter includes extended Latin, Italic, Cyrillic, Greek, and IPA scripts.